Haskell

Intro

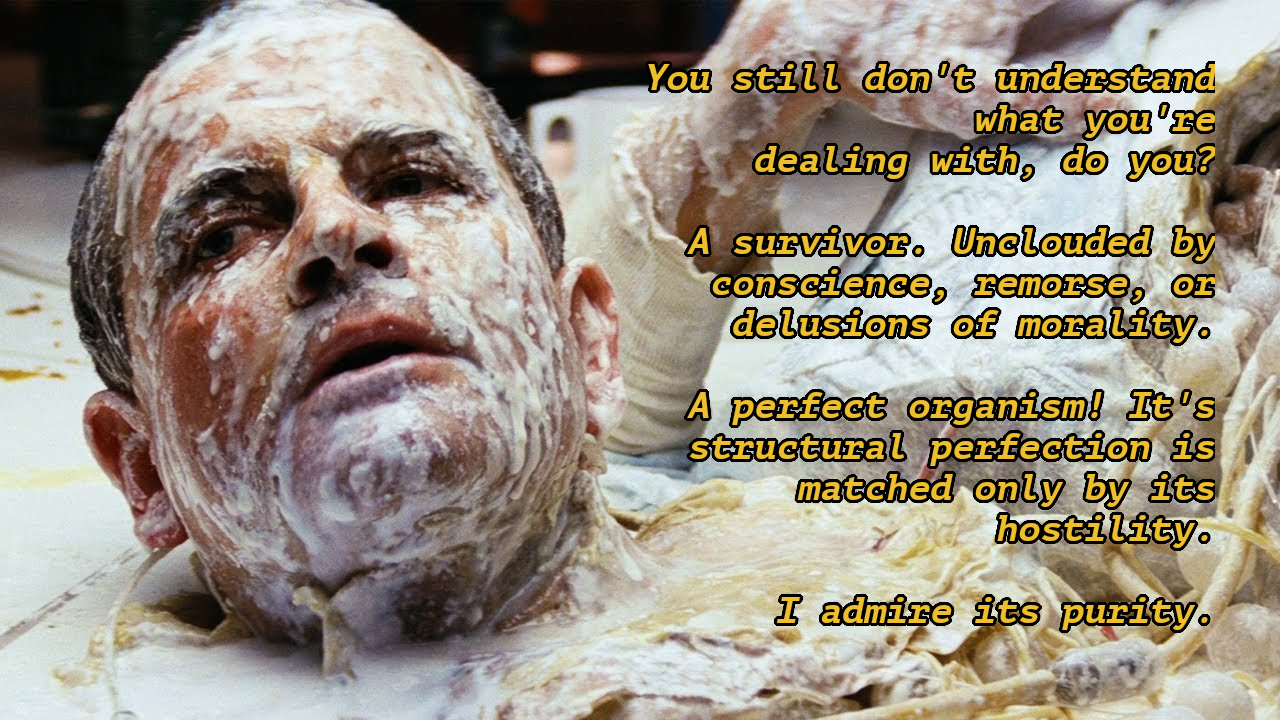

Hello world You still don’t understand what you are dealing with, do you?

A survivor. Unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality. A perfect organism!

It’s structural perfection is matched only by its hostility.

I admire it’s purity.

Alien 1978

It seems Ash was really talking about Haskell 😅.

Yes, it is a hostile language (at least from a certain point of view).

People who write books use tiles and descriptions that imply that their book is different. “Now you’ll finally get it” because “this book is written in such and such a way that will make it a no-brainer for you to finally get it”. They say that “it is not that hard”, that the problem is that “the other existing books are not easy for beginners” and so on and so forth.

Getting started with Haskell is harder than in some other languages. That is a fact. Let’s not try to hide it. Let’s acknowledge it and deal with it.

People say that Lisp is easy, that you learn the syntax in a few minutes Still, it takes uncountable hours of study (years) and practice to actually get good at it (although the same is true of any language, one could argue).

It doesn’t matter if it is hard or not. It is an amazing language, created and improved by people who do research in this area for more than 30 years (and counting). It also teaches one new ways of thinking, of accomplishing things and solving problems. It is also a very unique language (in many respects). It is worth studying and learning it. A new universe awaits!

Identifier names

Identifiers like xs or ys mean x or y in plural form, hinting it is some sort of list or collection of values.

Sometimes, a variation lox is also used (based on the book How To Design Programs ideas), meaning a “list of x”.

So we would have things like lon for a “list of numbers” or “lou” maybe meaning a “list of users”.

It all depends on the context.

Here’s one example:

myZipWith :: (a -> b -> c) -> [a] -> [b] -> [c]

myZipWith f xs ys = go f xs ys []

where

go :: (a -> b -> c) -> [a] -> [b] -> [c] -> [c]

go _ [] _ acc = acc

go _ _ [] acc = acc

go fn (x : lox) (y : loy) acc = go fn lox loy (acc ++ [(fn x y)])One important note is that some times we intentionally use bad identifiers (names of variables, functions, types, interfaces, whatever) on purpose.

We do this so that we are forced carefully think in terms of types and code, deeply contemplating their implications.

Good names, like add1 or filter give away what the code is doing (of course this is what we do for production code), but may defeat the purpose of a question or exercise.

Take a look at this piece of Haskell code:

h :: Integer -> Integer

h 0 = 1

h n = n * h (n - 1)What does the function h do?

You have to really read and understand what it does step by step to know what it is really doing.

What if I write it this way?

Show me!

factorial :: Integer -> Integer

factorial 0 = 1

factorial n = n * factorial (n - 1)Let’s try another one.

What does the function f do?

f :: (Eq a, Num a) => a -> a

f n = go n 0

where go n acc

| n == 0 = acc

| otherwise = go (n - 1) (acc + n)Again, with a better

Show me!

sumUpTo :: (Eq a, Num a) => a -> a

sumUpTo n = go n 0

where go n acc

| n == 0 = acc

| otherwise = go (n - 1) (acc + n)If we just see a nice name, it primes our brain to think like “Yeah, I understand this”, but some times, we don’t really understand it.

Again, for real, production code, we ought to spend whatever time it takes to come up with the best possible names. But when studying, depending on the purpose of the given question, exercise or situation, occasionally the good naming of identifiers defeats the whole goal.

The idea is that in certain situations, purposefully using non-meaningful names ends up forcing us to pay close attention to the whole code, flow, types, etc., making the entire experience harder, but much more prone to actually teaching us something.