Bash Redirections

Intro

Redirection is all about file descriptors (FD for short):

-

Standard input, or STDIN is FD 0.

-

Standard output, or STDOUT is FD 1.

-

Standard error, or STDERR is FD 2.

On most Unix systems, we have:

-

/dev/stdin -

/dev/stdout -

/dev/stderr

And even those are actually links to other special files on most unix-like systems:

$ file /dev/stdin

/dev/stdin: symbolic link to /proc/self/fd/0

$ file /proc/self/fd/0

/proc/self/fd/0: symbolic link to /dev/pts/7

$ file /proc/self/fd/0 /dev/pts/7

/proc/self/fd/0: symbolic link to /dev/pts/7

/dev/pts/7: character special (136/7)But from the user’s perspective, we don’t need to go that deep.

Shells offer shorthand syntax to work with those devices and file descriptors.

Programs can read input from STDIN or other sources, as well as send output to both STDOUT, STDERR or other destinations, like log files. A well-designed, well-written program will send output to whatever destination is makes sense at any given situation, allowing a more fine-grained control to users trying to collect, log, archive, filter, or simply read the program’s output.

Many (if not all) standard Unix and/or GNU tools send normal messages to STDOUT and error messages to STDERR.

When programs send messages to STDERR, they show up in the terminal as if they were standard, normal messages, but that is because shells attaches both STDOUT and STDERR to the terminal so we can read messages, be them errors or not.

For example, if we run the command nope, and such command (program) cannot be found, the shell informs you about it:

$ nope

-bash: nope: command not foundThat message is STDERR, but we see it in the terminal because by default, the shell attaches both STDOUT and STDERR to the terminal.

And we can redirect any error message (FD 2, /dev/stderr/) to the /dev/null black hole, a log file, or some other destination.

Read on.

Food for Thought

Consider the C programming language. When we do something like this, where is the output text sent to‽

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

printf("%s\n", "Hello, world!");

return 0;

}Unsure‽ What if I write it this way‽

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

fprintf(stdout, "%s\n", "Hello, world!");

return 0;

}Similar with the shell.

We kind of know and assume echo hello or printf %s\\n 'Hi will somehow “print the output”.

It is easy to just take it for granted and not pay much attention to it.

Understanding in Practice

Bash (and all shells, for that matter) performs redirection by default in almost all situations.

That is why we can simply do things like echo hello, for example and see the text printed on the terminal.

But let’s pretend for a moment that we have to perform all redirections manually.

As you’ll see, this is a great way to understand how things work.

In all examples that follow, be mindful that the order in which redirections are applied is important.

A Note On Default File Descriptors

When > is used to redirect output (like in echo hello > ./out.log), that lonely > is actually short for 1>.

When redirecting output, the default, implicit file descriptor is FD 1, or /dev/stdout.

When < is used to redirect input (like in sed -n '/main/p' < ./main.c), that lonely < is actually short for 0<.

When redirecting input, the default, implicit file descriptor is FD 0, or /dev/stdin.

Send Output to STDOUT

We’ll use bash’s builtin printf to get started.

It sends output to STDOUT (or to a variable, with the -v option) unless it errors out due of an invalid format option or something else, in which case it sends the error message to STDERR.

We can capture its STDOUT with file descriptor 1 and then redirect that as we see fit.

Get printfs STDOUT and redirect that to /dev/stdout:

$ 1> /dev/stdout printf %s\\n hello

helloAnd the above example is in fact just the same as this:

$ printf %s\\ hello

helloGet printfs STDOUT and redirect that to ./out.txt:

$ 1> ./out.txt printf %s\\n hello

(no output)

$ cat ./out.txt

helloNo output because the output was redirected to ./out.txt.

Then we used cat and observed the output had really been sent to that file.

Get printfs STDOUT and redirect that to /dev/stderr:

$ 1> /dev/stderr printf %s\\n hello

helloIt still just prints to the terminal because by default the shell attaches STDIN, STDOUT and STDERR to the terminal.

And this also sends STDOUT to STDERR, but now using the special bash’s syntax:

$ 1>&2 printf %s\\n hello

helloGet printfs STDOUT and redirect that to /dev/stderr and then redirect that to /dev/null:

$ 2> /dev/null 1> /dev/stderr printf %s\\n hello

(no output)No output because STDERR was consumed by the dark side of the force (/dev/null).

Get printfs STDOUT, redirect to /dev/stderr and then redirect that to ./err.log:

$ 2> ./err.log 1> /dev/stderr printf %s\\n hello

(no output)

$ cat ./err.log

helloNo output because STDERR was redirected to a text file ./err.log.

Then we used cat and observed the output was really sent to that file.

And the above is the same as this:

$ 2> ./err.log 1>&2 printf %s\\n hello

(no output)

$ cat ./err.log

helloIn the above examples, a mix of bash’s syntax and standard Unix-like special devices were used. In practice (command line, shell scripting), we’ll mostly stick to the shell’s special syntax most of the time.

Redirect STDERR

First, let’s run a command that doesn’t exist:

$ nope

-bash: nope: command not foundIf that message was sent to STDERR, we can redirect it, for instance, to /dev/null to ignore it:

$ nope 2> /dev/null

(no output)Or to a file for later inspection:

$ nope 2> ./err.txt

(no output)

$ cat ./err.txt

bash: nope: command not foundRun ls on a non-existing file, which will print an error message:

$ ls ./i-dont-exist

ls: cannot access './i-dont-exist': No such file or directoryIf ls sends error messages to STDERR (which it does), then we can redirect that message to whatever destination we see fit.

If we don’t want to display the error, but instead send it to the black hole, we then send STDERR (file descriptor 2) to /dev/null:

$ ls ./i-dont-exist 2> /dev/nullOr to a log file:

$ ls ./i-dont-exist 2> ./err.log

(no output)

$ cat ./err.log

ls: cannot access './i-dont-exist': No such file or directoryAnd the redirection 2> destination part does not need to came last.

It just feels more natural to write it last, but it can be even written before the command itself:

$ 2> ./err.txt nope

(no output)

$ cat ./err.txt

bash: nope: command not found

$ 2> ./err.log ls ./i-dont-exist

(no output)

$ cat ./err.log

ls: cannot access './i-dont-exist': No such file or directoryAnd remember that the shell sets up redirections before commands are run. So one could argue it even more closely matches to whatever the shell even does internally.

Redirect All Messages to /dev/null

Sometimes we just want the terminal to be silent and not pollute the output with noise that may not matter for a given situation and ends up taking our attention away from whatever we are doing. See here one example:

|

I do not advise hiding terminal messages in general, but sometimes it may be desirable for specific situations. |

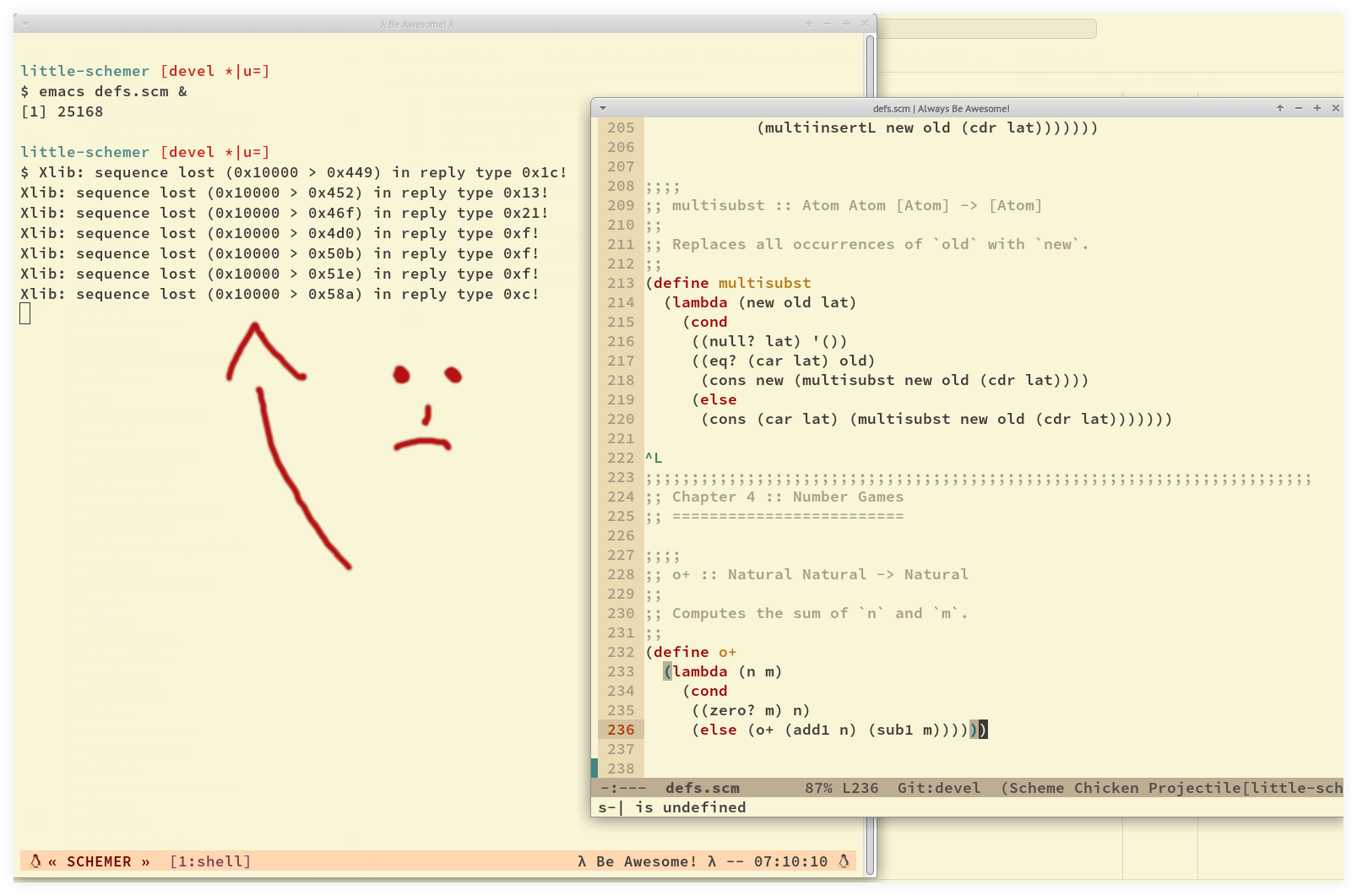

I just want to open emacs on my little-schemer directory to work on the exercises from the book The Little Schemer, but those messages annoy and distract me.

For bash >= 4, we can simply do:

$ emacs ./main.scm &> /dev/null &Of course one may prefer to redirect to a text file instead:

$ emacs ./main.scm &> ./log.txt &Note we used the &> bash syntax.

For bash < 4 or other shells, a more portable approach is to use the standard 2>&1 syntax:

$ emacs ./defs.scm 1> /dev/null 2>&1 &And this more closely matches the order in which things happen behind the scenes:

$ 1> /dev/null 2>&1 emacs ./defs.scm &Or

$ emacs ./defs.scm > ./out.txt 2>&1 &Again with the syntax which more closely matches the order in which things happen (redirections are setup first):

$ 1> ./out.log 2>&1 emacs ./defs.scm &In all cases, the final & is used to free the prompt as the process then is run in the background.